Warren Angus Ferris is my great-grandfather (x3) on my father’s side. He was an explorer, adventurer, surveyor, and a skilled writer. Much has been written about him and his travels. He documented his explorative adventures while working as a trapper with the American Fur Company from 1830-1835 in a diary entitled, “Life in the Rocky Mountains” which was published serially in 1842-1843 in the Western Literary Messenger by Ferris’s brother, Charles Drake Ferris.1 Charles became editor and part owner of the publishing company in 1842 and felt great enthusiasm for his older brother’s narrative which has served of priceless value to students of the early West.

This is the story of Charles Drake Ferris. His story is equally interesting to that of his brother, but relatively unknown. He was of Puritan and Quaker ancestry. Eight of his forbears, John Alden, Sr. among them, were in the Mayflower company. His paternal grandfather, Warren Ferris, was a brigadier-general of Militia in Washington County under then Governor Morgan Lewis in 1806 during the American Revolution.2 His mother’s ancestry traced back to the family of Lady Jane Grey, known as the “Nine-days Queen of England”.3

His family ancestry can be traced to one Samuel Ferrerrs of England. Samuel’s son Zachariah came to Charlestown, Massachusetts and married Sarah Blood. They were among settlers who took arms in the Indian disturbances of 1675-1676, known as King Phillip’s War. In August 1710, Samuel set forth on an expedition against Port Royal in Queen Anne’s War, where it is believed that he perished. It is Samuel who changed the spelling of the family name to Ferriss, which was changed to Ferris 2 generations later.4

Angus Ferriss and Sarah Gray were married on January 28, 1810 in Queensbury, New York. This bond brought together 2 pioneer bloodlines who dreamed of joining the westward movement. On their attempt to move westward, they settled in Erie, Pennsylvania, where they had 2 children: Warren Angus Ferris and Charles Drake Ferris. Charles, the second son, was born on December 5, 1812. Angus Ferriss died suddenly on September 10, 1813, leaving Sarah a widow.5

Seeking a better situation, Sarah and her 2 boys moved to Buffalo. The city was young and just arising from its ashes from the destruction resulting from the British and Indians in the invasion of December 30, 1813. There she met Joshua Lovejoy, a merchant and recent widow. They were married on August 13, 1815 and set up home in a little settlement situated near the mouth of Buffalo Creek, at the foot of Lake Erie. They had 4 children: Joshua Ferris Lovejoy, Ruth Lovejoy (died as an infant), Sarah Perkins Lovejoy, and Maria Louisa Lovejoy. Maria Louisa married the landscape artist Laurentius Sellstedt in 1850. Times were particularly hard for the Lovejoy family in Buffalo. They had many mouths to feed and work was scarce. Snow fell as early as May and hard frost came as late as July. In 1816, conditions were so harsh that it seemed winter had come 3 months early. The year was known as the “year without a summer” causing major food shortages due to the harsh weather conditions. In 1824, Joshua Lovejoy was stricken ill and died on September 5th at the age of 53. Sarah was once again a widow at the age of 39. A skilled seamstress, she was able to make a living for herself and her children, ranging from age 1 to 14. She purchased a 5-acre lot of land west of Chicago Street and there the family made their home. Her children received a classical education for the times and all had a natural talent for writing.6

The children were raised in a home near the Buffalo waterfront. The waterfront activities fascinated the Ferris boys. Young Warren and Charles most likely witnessed the first steamers to sail the Great Lakes. In October 1825, they attended a great celebration of the completion of the Erie Canal. With the opening of the canal began a period of swift development. Many settlers desired to move westward, and Buffalo became a funnel for their travels. Pioneers came to Buffalo to begin their long, arduous journeys west to the territory beyond.7

Warren and Charles were enchanted by the spirit of the times and the lure of the great West. At the age of 18, Warren Angus Ferris decided to venture out for himself. He worked in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and eventually St. Louis. In February 1830, he joined the first expedition of the American Fur Company to the Rocky Mountains and set out on the adventure of his life. He documented his 5 ½ years of exploration in a journal which has served as a valuable source of information about the journeys into the great West. He also drafted a map entitled “Map of the Northwest Fur Country” in 1836.8

In 1831, their younger half-brother Joshua Lovejoy also left Buffalo for the Michigan Territory. Charles, 2 years younger than Warren, remained at home to provide primary support for his family. As time would reveal, it was his inherent nature to serve his family and ensure their well-being. In 1832, Charles wrote a letter to Joshua describing the spread of cholera in Quebec and predicted an epidemic in Buffalo. His prediction came to fruition, but his family was fortunate and were spared.9

Despite Sarah and Joshua’s pleading against marriage, Charles Ferris wed Hester Ann Bivins on May 5, 1834. They came to live with the Lovejoy family in their Seneca Street home in Buffalo. Charles was employed in the post-office as a clerk and made a modest wage. The period was one of great financial strain in Buffalo. There was profit to be made in the sales of land, but the family could not entertain selling because they were engaged in a long, drawn-out law-suit with their half-brother, Henry Lovejoy, over the division of their property.10 This struggle would create great strife for the family for years.

Texas offered great opportunities at the time. Large grants of land were being offered as inducements to new settlers. The spirit of new beginnings excited Charles and in October 1835, he left his position as clerk and began executing his long-held, cherished plan to seek his fortune in Texas. At this time, tension against Mexican tyranny was mounting rapidly in Texas. Conditions were not amenable for his pregnant wife to travel with him, so he set out on his adventure alone. Five months later, his first child, Charles Warren Ferris, was born.11

Charles traveled to Texas to volunteer in the revolution, taking with him letters to Sam Houston and Don Lorenzo de Zavala, the patriot who became Burnet’s vice-president. He joined the Texian army shortly before the battle of San Jacinto. 12 It is of differing opinion as to whether Charles Ferris actually took part in that decisive battle and, to date, there is no official evidence proving that he was present. However, there are multiple correspondences, literature, and circumstantial evidence supporting that he was a participant. In a letter Sarah Lovejoy (sister) wrote to Joshua Lovejoy (brother) on June 27, 1836, saying: “The last letter we had from Charles was dated the 22nd of April, the day after the battle of San Jacinto and Santa Anna’s capture. He was then well – delighted with the country and in good spirits – he had thought their next movement would be to San Antonio to endeavor to retake it.” The letter continued: “Horace Chamberlain is in Texas and was with Charles April 23. When he wrote home, he said that Charles had a narrow escape in the battle of the 21st – in the heat of the engagement a Mexican at a distance of 5 paces fired his musket at him which he avoided, but his horse was frightened and threw him. However, for once good luck was his; he alighted on his feet, and the Mexican rushed upon him with his bayonet, but Charles was too quick for him and saved his own life, with the loss of part of his rifle. Charles is aide-de-camp to Governor Robinson. He writes that he shall have about five thousand four hundred acres of land to repay him for going there.”13

The reference in Sarah’s letter to the “next” movement of the army indicates that Ferris had been at San Jacinto and had knowledge of the army’s strategic plans. The detailed account of April 23rd indicates that Horace Chamberlain, if not an eye-witness at San Jacinto, was provided the story from Charles within 2 days of the battle of San Jacinto. Chamberlain’s account suggest that he had no doubt that Ferris was at the battle.

It is also likely that Charles Ferris may have been the “Col. Ferris” that James W. Fannin dispatched to Lt. Gov. James W. Robinson on February 28, 1836, with the information that Fannin’s troops had made an unsuccessful attempt to reach Texas and had returned to Goliad.14 It is also documented that Ferris served as a spy under Mosley Baker and informed Baker of the location of Mexican troops.11

Seven years later, while Charles was editing the Western Literary Messenger, the publication carried an unsigned article that undoubtedly was written by Charles. A family notation on the article ascribes it to him. In it he speaks highly of Colonel Almonte, the minister from Mexico. His words describe vivid details of the horror of the battle and the character of which Almonte demonstrated during the Mexican loss, and concludes with an account of his noble behavior at the Battle of San Jacinto:

“When Santa Anna invaded Texas in the spring of 1836, Col. Almonte accompanied him in the capacity of aide-de-camp, and in the disastrous affair at San Jacinto behaved with remarkable courage and address. Immediately upon the line of his army being broken by the desperate charge of the Texians, Santa Anna fled from the field of battle, followed by all his mounted officers and cavalry. Not so Almonte.

On foot he headed the broken force of the Mexican infantry, which he partly rallied and held in something like order during the remainder of the action, exposing his person constantly in the hottest of that deadly fire, before which his soldiers fell like corn beneath the sickle, heaping the ground around him with their corpses. When further retreat was impossible and resistance had become the mere madness of despair, but not till then, did Almonte think of surrender. His own force was by this time reduced to a bare remnant of some two hundred and fifty or three hundred men, out of above seventeen hundred with which the Texian attack had been met, and more than that number of the enemy, flushed and eager with conquest, and burning with hate and revenge, were pressing him close, and pouring in a heavy and most destructive fire. Few men could under such circumstances have displayed a more cool and intrepid heroism than did Almonte, and it was beyond question the means of saving his own life and that of his followers. There was every reason to think that the infuriated Texians were determined to avenge the massacre of Travis and Fannin, by a literal extermination of their defeated foes. His men were falling thickly on every side, resistance was out of the question, the battle had already become a mere massacre, there was no time for hesitation or reflection, delay was death. Such was the situation of affairs when Col. Almonte, with singular presence of mind and the most devoted and exalted courage, seized a flag-staff, to which he hastily fixed a white handkerchief, and advanced himself (his affrighted soldiers following and clinging to him as their only hope and stay) through the literal hurricane of bullets that poured in upon them, and with calm intrepidity confronted the mad host of opposers, displayed and called attention to his signal, and surrendered himself and the shattered remnants of his force prisoners of war. It is doubtful if a single man would have been spared but for the surprising bravery and composure of Almonte, which commanded the respect of the victorious Texians, calmed their excitement, and cooled their animosity. There was a noble and lofty chivalry in this self exposure and devoted daring, akin to that of Napoleon at Lodi, which they could not help admiring and sympathising with. The firing ceased, the surrender was accepted, and the survivors saved. Ourself a witness to this act of heroic gallantry, it gives us pleasure to record it.”15

Although there is no documented record, the Ferris-Lovejoy family has always believed that Charles fought at San Jacinto. Sarah Lovejoy wrote in her diary on April 21, 1837: “One year ago this moment and Charles was in the furious battle of San Jacinto.”16 On July 18, 1838, Warren Ferris wrote to Charles: “I am doubtful about your getting all the land you expected though besides the league and labor, you will get a donation of 640 acres for being at San Jacinto, and perhaps military scrip for services if you demand it. There has been much fraud practiced in some of the Land Offices and hundreds of fraudulent certificates issued by insomuch that a good portion of the public domain will fall into the hands of swindlers, but perhaps it will not injure the country much. Land will rise rapidly in value and the more owners there are to the soil the more easily will the National debt be paid by the people.”17

Charles Ferris’s name doesn’t appear on any lists of San Jacinto veterans.18 He did not receive the donation certificate for 640 acres of land awarded to those who proved that they had participated. His family did receive by special act of the Texas Legislature in 1877 a grant of 960 acres for his services in the Army of Texas. However, there is no record that he or his heirs ever claimed a donation certificate for land.19 Had there been proof of his involvement in the battle, his heirs would have been entitled to a total of 1,600 acres of land.

There has been some investigation in 1900 and later to determine if Charles Ferris was involved in the battle. Mr. Louis Wiltz Kemp, former President of the Texas Historical Society, did not include Charles Drake Ferris in the list of veterans present at San Jacinto. It is important to note that he also omitted Horace Chamberlain’s name as well.20 It is recorded in Sarah Lovejoy’s letter that Ferris and Chamberlain were together on April 23, 1836 and that Chamberlain wrote in a letter to his father sharing the story of Charles’s encounter during the battle as noted in Sarah Lovejoy’s letter to Joshua Lovejoy.13 In his letter, Horace Chamberlain wrote: “Charles D. Ferris, formerly of Buffalo, is here, and belongs to the army – he is aide to Governor Robinson. He was in the engagement, and narrowly escaped death. In the first charge on the enemy, he was attacked by a Mexican soldier, who attempted to bayonet him, seeing Ferris’ rifle had missed fire. At the charge made at him by the soldier, his horse sprang to one side and threw him, but fortunately falling on his feet, he killed the advancing foe with the butt of his gun. Three days after the battle, I visited the field, which was literally covered for ten miles with the dead. Santa Anna has offered to recognize the independence of Texas and pay the expenses of the war, on condition of being set at liberty.”21 Chamberlain’s account was published on June 15, 1836 in the Daily Commercial Advertiser in Buffalo, New York.

The Ferris-Lovejoy correspondences cited provide evidence of Ferris’s role in the battle. Historians did not have the benefit of these cited correspondences. Also, Mr. Kemp did later supply some information indicating that Sam Houston’s list of soldiers may not have been complete.21 According to the list of San Jacinto veterans by John J. Linn, neither Chamberlain nor Ferris are listed in the “Reminiscences of 50 Years in Texas” written in 1883, nor are they listed in D.W.C. Baker’s “A Texas Scrapbook”, written in 1875.19 They are not listed in supplementary lists of veterans.

It is noteworthy to add that Dr. William P. Smith, wrote a letter on July 20, 1858, to Richardson and Company which was published in the Texas Almanac.22 In the letter Dr. Smith addressed the issue that General Houston’s published account of participants of the battle omitted deserving soldiers who had provided service at San Jacinto. He noted that soldiers left in charge of the sick, the baggage, etc., at the upper encampment were omitted. Dr. Smith stated that he was personally left in charge of some 60 soldiers sick with the measles. He points out that he received the 640-acre San Jacinto land donation and that it was an injustice that deserving soldiers were omitted from Houston’s list.

It is also possible that Ferris’s name was omitted due to loss of records. The Archives of Texas are made up of documents and records from the various periods of Texas history including Mexican dominion, 1821-1836; Republic of Texas, 1836-1845; and the State of Texas 1846-present. In 1836, in attempt to keep the Texas documents from falling into Mexican hands, they were moved by the interim government as Sam Houston’s retreating army moved eastward; some of the archives were lost. In 1836, the documents were moved from Columbia and then to Houston in 1837. In 1839, a fleet of wagons brought the documents to the new capital at Washington-on-the-Brazos, thus initiating the Archives War. In 1845, the treasurer’s office burned, causing irreparable loss of the muster roll of the soldiers of the Texas Revolution. In 1881, the capital burned resulting in a slight loss of documents.23

There are numerous pieces of evidence supporting that Charles Ferris participated in the Battle of San Jacinto: 1) the article published in the Western Literary Messenger, identified almost beyond doubt as that of Charles Ferris, describing himself as a witness of Colonel Almonte’s character during the battle; 2) Charles’s reference to “the next movement” of the army in a letter to his sister written a day after the battle; 3) a contemporary and circumstantial story from Horace Chamberlain; and, 4) family correspondence acknowledging his participation. Collectively, these findings indicate that Charles took part in the battle that decided Texan independence.

Following the Battle of San Jacinto, in May 1836, Charles was in camp at Harrisburgh, Texas. He was given a letter of introduction to General Thomas J. Rusk, then in command of the Texan Army. The letter was written by Lt. Governor James W. Robinson and read: “Permit me to introduce to your favourable notice my friend Col. C. D. Ferris. He proposes raising a company of Cavalry, and as he understands the sword exercises and other duties of a corps of Cavalry and is a young man of classic education and morals, habits and tried valor, I think he will be an ornament to the Army.”22 Robinson’s reference to “tried valor” was written within a month of the Battle of San Jacinto.

On May 29, 1836, during the retreat of General Houston, eastward from the Colorado River, General Thomas Rusk ordered approximately 20 well-mounted, well-armed rangers to scour the coast in search of enemy activity. The group included Major Isaac Burton and Charles Ferris. Four days later the party learned that a suspicious vessel bearing Mexican colors was in the Bay of Copano. The rangers enticed a small boat from the enemy ship ashore by displaying the Mexican flag. They then boarded and captured the vessel called the Watchman. They loaded their horses on the vessel and traveled coastwise to Brazoria where they captured the Comanche and the Fanny Butler vessels, also carrying Mexican army provisions. These successful missions came at a time of poor spirits due to the retreating Texan army. The citizens of Brazoria bore Major Burton on their shoulders and voted that he and his gallant rangers should be called the “Horse Marines”.25

Charles returned to Buffalo in the summer of 1836, intending to go back to Texas after settling personal affairs. His brother, Warren Angus, had returned to Buffalo from his Rocky Mountain adventures, and was preparing his journal for publication. The young brothers worked together and the journal was completed by October, 1836. They submitted it to Carey Lea & Blanchard of Philadelphia. That company had published Washington Irving’s “Astoria” and had accepted Irving’s “Rocky Mountains” based on Captain Benjamin Bonneville’s journal. After months of consideration, the publishers declined to publish Warren’s journal and said: “Though much disposed to think it would sell, we feel compelled owing to our numerous engagements in other works, to decline undertaking this.”26 Although discouraged, Charles still believed that the journal was a valuable piece of information and could also be profitable if published.

Charles and Warren returned to Texas in 1837 to seek new ventures and pursue profitable enterprise. They both began surveying careers at this time. Charles joined his friend Major Isaac Burton in Nacogdoches, where they organized a surveying expedition to the wild country near the mouth of the Trinity River.27 On their return, they made an arrangement that Charles should edit the Texas Chronicle, a Nacogdoches newspaper owned by Burton, and the latter should continue in the surveying business. They planned to share the profits equally. Warren Ferris was eventually responsible for the first surveys of land in what is now the city and county of Dallas. He was never recognized for his efforts, because John Neely Bryan was given the credit.28

Charles returned to Buffalo later in 1837, intending only a short visit. He was then in his mid-twenties. Within 4 days of his arrival, he was arrested and later released for suspicion in being involved in the escape of Lyman Rathbun. He was not deterred by his difficulties with the law and turned his focus on returning to Texas. His spirit for Texas was fierce and he felt tremendous passion for the affairs of the young republic. In August 1837, he revealed his heart-felt emotions by writing a verse of nine stanzas on the massacre of Col. James Fannin and his men by the Mexicans.29 In reading, one can feel the regret he felt for the slaughter at the Massacre of La Bahia and for the vengeance Texians sought at the Battle of San Jacinto, which he believed was justified.

Charles Ferris submitted his poem anonymously to the Commercial Advertiser for publication. It was declined with the following statement and never published:

“Fannin, or the Massacre of La Bahia” is declined. The fair writer – for the chirography resembles that of the gentler sex – might find other and more fitting subjects for her muse. We can hardly believe that “the hosts of bright seraphs, and angels on high,” much less the deity, who is irreverently introduced, find much to approve, or sympathise with, in the character and events of the Texas contest. There is an impiety in the language of this communication, which even the license of poetry cannot excuse. We are sorry to see talents of no common order thus employed.”29

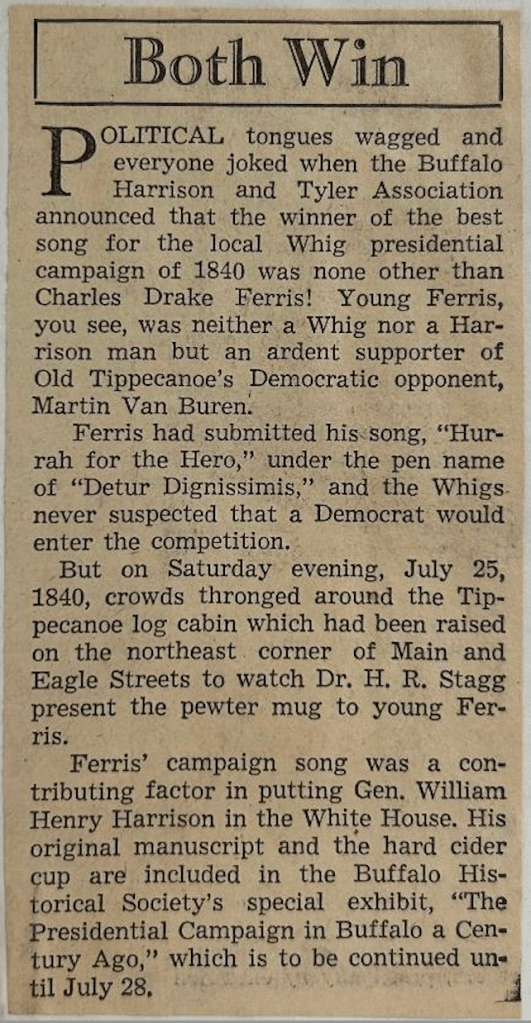

Charles Ferris intended to return to Texas, but hard times and family responsibilities prevented him from ever returning. He had promise of land and a hopeful future in Texas, but never obtained the money to return due to family obligations. His literary interests projected him toward the profession of writing and editing. He became associated with Thomas L. Nichols in publishing a weekly paper called The Buffalonian. During the presidential campaign of 1840, partisans of Harrison and Tyler, in attempt to defeat Van Buren, organized a Tippecanoe Log Cabin Association and offered a prize to the author of the best campaign song.30 Charles Ferris submitted a song and won the contest. His sister, Sarah Lovejoy wrote on September 17, 1840: “Charles is quite a literary person now; and has as much vanity as any one ever pretended to have (I say the last in a whisper for it might make him mad and I hate cross faces). He has written a prize song this summer- won the Log Cabin Cup-made a speech when it was presented and had three rounds of applause! Besides this, he has written two plays, one a farce, the other a grand tragedy in five sets, after the most approved fashion, called “The Ottawa Chief or the Siege of Detroit.” This last was performed a week since, and murdered as Charles said- I was not there- one of the actors, who took the longest part, the principal character, was drunk and didn’t know the lines. Next week it is to be re-enacted.”31 The play was repeated on the following evening, but not again.

Charles was at the peak of his literary production in the early 1840’s. He became devoted to social reform and began editing The Phalanx daily and weekly for Mr. Albert Brisbone. This was the first daily paper this side of the Atlantic devoted exclusively to social reform and advocacy of the principles of Associationism as evolved by Charles Fourier. The paper folded at the end of 6 weeks. Sarah Lovejoy remarked on the paper’s goals that “they are going to reform the world. I hope they succeed- but I have my doubts.”32

Sarah Lovejoy and Charles Ferris collaborated on a story entitled, “The Doom Averted” which was published by The Bristol’s Gazette & Herald of Health. These literary activities did not pay well and Charles had to supplement his labors of his pen by working in the post-office. Sarah wrote on May 15: “Charles has been in the post office last week and this, during the absence of one of the clerks; but there is no business of any consequence that he can do, and it is impossible for him to get enough money to go to Texas. The care is constantly wearing on his health – he has always plenty to do. His pen is forever employed. One wants him to write such an article, and another its opposite – for these he seldom gets cash – vulgar cash- but they have won for him a reputation for talent which is worth some sacrifices.”33

In 1841, the superintendent of Buffalo schools, Oliver G. Steele, hired Charles to write a work entitled, “The Balance Sheet.” The 92 page book was written, according to family tradition. The subtitle reads; “A moral and instructive story for youth, designed to show the advantages of persevering industry, strict integrity, and good moral habit, and the necessity of a regular system of keeping account; and also to illustrate the evil consequences of crime and the inevitable tendency of vicious inclinations.” The story mirrored Charles’ life, the son of a poor but honest widow, oppressed by a rich and grasping enemy, who is virtuous and triumphant in the last chapter.34

Another work by Charles Ferris is the book entitled, “Pictorial Guide to Niagara Falls” published by John W. Orr. Although his name doesn’t appear in its pages, research in 1941 by Mr. Walter McCausland proved that he was the author.35

Charles became editor and part owner of the Western Literary Messenger in July 1842. His most important literary service performed, was the publication of Warren Angus Ferris’ journal, “Life in the Rocky Mountains.” The journal ran serially in the Western Literary Messenger from January 1843 until May 1844. This process preserved the important record of the early fur trade, the only know account of those days written by a representative of the American Fur Company.

As mentioned previously, it was during his direction as editor of the Western Literary Messenger that Charles wrote the article praising Col. Juan Almonte, then minister from Mexico to the United States. It detailed how Col. Almonte tried to rally the Mexicans at San Jacinto after Santa Anna had fled the scene. The article detailed Almonte’s gallantry in the face of “the infuriate Texians, determined to avenge the Alamo and Golidad”. Ferris wrote the account “as ourself and witness”, thus providing additional written evidence that he was present at the battle of San Jacinto.15

The Western Literary Messenger received a respectable circulation, but subscribers had difficulty paying the $2 subscription price. Finances were stained, and in October 1842 Charles sold the printing materials of the Messenger office and in July 1843, he sold his share of the business. With a new owner and editor in place, “Life in the Rocky Mountains” suffered severe editing as the new owners did not share the same enthusiasm of Charles Ferris for his brother’s journal. Thus, unfortunately, there was a loss of valuable information of interest to students of the early West.36

In 1844, after the nomination of Polk, James Stringham, owner of the Courier, hired Charles Ferris as editor. He described Ferris as an industrious and vigorous writer. The arrangement ended with the election. Although his work was not signed, Stringham noted that Ferris’s work was marked by an asterisk. These editorials are mostly bitter attacks against the rival candidate, Henry Clay.37

Charles’s literary ventures were not adequately profitable to support his family, which included his mother, 2 sisters, his wife, and 4 children. He was forced to seek employment again in the post-office. Their lives were filled with constant struggle, misery, and despair as revealed over and over in Sarah’s diary entries. In March 1846 he wrote to Warren, who was back in Texas. The letter is a summary of his life’s work, his sense of lost opportunity, and reveals his deep moral character. In it he confesses his heart’s deepest desire to return to his beloved Texas:

“I have devoted my life and made a sacrifice of every opening prospect to be near and take care of and protect mother and her daughters, and I do not regret it. To the little I have done, all I could do, they are doubly welcome, and if by all my sacrifices and all my labors I have dissipated the blackest of the clouds that darken upon their earthly careers, I have ample reward. I have defended their rights for them, protected them, kept them at least in a situation of comparative comfort and independence, and this is my consolation for a life in other respects wasted. It is hard and I have felt it, too, how deeply none can ever know, with ambitious aspiration of no common force and a conviction of being able, with opportunity to achieve something worthy of these aspirations, to curb one’s wishes and chain himself to humble conditions and a dull ration of toil with a scant remuneration and nothing to look forward to, when on another field, and without this clog, what might not patience and assiduity have reached. But I have no regrets to reproach myself with; I saw all this and made up my mind in view of the whole premise. I knew that if I said here I had nothing to expect, that if I left my sisters and mother it would be leaving them to privation and dangers I could not dream of exposing them to, that if I persuaded them to sell their property and move with me to a region where there was a chance of establishing myself and gaining some distinction in the world, a mischance, an unfortunate investment, a defective title, or any one of the thousand mishaps and errors to which all me are liable, would expose me to reproaches that I would rather die a thousand times that incur, and so I gave up all my own prospects, stifled the aspirations after distinction that would come up in my breast, and with a calm deliberateness bound myself to the course I have taken. I do not expect the sacrifices I feel that I have made to be compensated in any shape or to be appreciated or understood even, and so I would have it….I would have them think that I never had a thought or wish and never cherished a hope but what had had a fair chance of fruition here while I have been chained to their side as it could have had elsewhere. It is enough that I feel that I have done my duty, that they esteem that I have done it without any sacrifice of prospects or inclinations, and that there is one person in the world, you, my brother, who can sympathise with me, and by whom I can be fully understood… But enough upon a subject that I do not like to dwell upon, the past; and let me take a glimpse of the future. It is probable that Louise will be married in a year or two, and that mother’s and Sarah’s property can by that time be put in a situation to yield them a steady income sufficient for their support. Then the problem of their destiny can be read, and I shall have opportunity to pursue my own. Then, on that quiet plantation on which I have pictured myself in Texas, under its beautiful sky and its’ safe climate, I hope to find rest and opportunity to spend the rest of my days in a kind of literary ease, taking exercise enough for health, and having sufficient occupation in the care of my herds and the education of my children; such is the history, the situation, and the hope of your only brother.”38

In addition to feeling the constant, hopeless burden of family responsibilities, Charles was in poor health. He left Buffalo in October 1849, providing little information of his plans to his family. He communicated rarely with them, but in the fall of 1850 he wrote to let them know he was in Canada and that he was in better health. The family never heard from him again.39 On May 21, 1853, Sarah Lovejoy (sister) wrote to Warren Ferris:

“Until the next June (1851) we heard no more, when the merchants in St. Peter’s wrote that he had left Sidney in Cape Breton for that place on the 24th of December in ‘50 – about which time terrible storms swept the western coast of the Atlantic – and as five months had elapsed without the vessel reaching that port, and as the owners of the ship in Sidney had received no intelligence of her, they could not but consider the vessel lost with all her passengers. Since then we have heard from them several times, but no tidings of the ship Unicorn have ever come to hand. And yet there are so many miraculous escapes at sea, that I cannot quite give him up. But if I never see him this side the grave, I bear the highest testimony to his worth as a son and brother. If it had not been for his unwearied watchfulness and unceasing exertions we never could have retained one foot of the land we now hold.”40

On August 24, 1855, Warren wrote back to his sister Sarah. He stated that “in your last you stated that Charles had entered on board of some water craft bound for Canada and not having been heard of the vessel, was supposed to have foundered at sea. Now as vessels some times are driven far from their course and wrecked upon desert islands, where the mariners might support their existence for months or even years before an opportunity offered to find a conveyance home. I have still hoped that you would hear from him living, if however, such is not the case, it would be vain to indulge any further hope.”41

Historical searches and sources in Nova Scotia and Montreal have no record of a lost ship by the name of Unicorn. Lloyd’s Register of Shipping Vessels shows a sinking vessel named Unicorn abandoned off the coast of Portugal on November 10, 1850. The ship was sailing from Philadelphia to Londonderry, but the crew were rescued. A second vessel named Unicorn was abandoned while in transit from Liverpool to St. John, New Brunswick, but the crew and passengers were rescued as well. A third Unicorn vessel from that time was know to be sold to the Portuguese government in 1846.42 Thus, it seems that the ship that Charles Ferris was thought to have perished with must have been a small vessel involved in coastwise trade, whose loss went undocumented. However, there is also no conclusive evidence to prove his life was lost at sea.

Thus ends the chapter of Charles Drake Ferris’s life as information provides us. The family letters reflect that they hoped he had not perished at sea and that they held steadfast for a happier ending to his story. Sarah’s testimony to his “worth as a son and a brother” speaks to his devotion and sacrifice for his family. This is significant, as Charles felt personal regret for never reaching his ambitious aspirations. His family, however, held him in the highest esteem and cherished his devotion. He was certainly a man of impeccable moral character! He had a longing desire for adventure and tremendous intellectual curiosity. When provided the freedom to pursue his desires, he lived life largely and his deeds as a man, as an adventurer, and as a soldier should be honored. His family obligations prevented him from pursuing the adventures he yearned for, and although he never obtained riches and lasting fame, his personal integrity was unwavering. He longed to return to Texas, a land he deeply loved. In more favorable circumstances, he would have returned with his family and lived out his life in Texas. Although his time in Texas was short-lived, he made valuable contributions to the efforts in achieving Texas’s independence from Mexico. His participation in crucial events in the Texas revolution should be recognized.

Charles Drake Ferris was an accomplished man who was not boastful of his life’s accomplishments. Much of his work was submitted anonymously. His contributions as a soldier went unrecognized. His reward for service went unclaimed. His life ended in a shadow of mystery. It seems that the word “understated” best describes his life’s story. So many questions remain unanswered about Charles Ferris’s life. Was he present at the Battle of San Jacinto and deserving of the land donation awarded to the participating soldiers? What happened to Charles Ferris when he left his family in 1849 when he was still a very young man of 37 years? Did he leave due to perpetual poverty and despair, and if so, did he start a new life somewhere else? It is apparent that his heart’s desire was to return to Texas. Did he or his heirs claim the land donation he earned as a soldier serving for the Army of Texas? It’s possible that these questions will never be answered decisively, but by telling his story, perhaps it will rekindle the curiosity and inspire others to inquire and pursue his story in greater depth. This great niece (x3) hopes that one day, Charles Drake Ferris will be recognized as a veteran of the Battle of San Jacinto.

Written by Anna Christine (Boles) Cohen

Acknowledgements:

I would like to acknowledge and express my gratitude to Susanne Starling and Walter McCausland for devoting years of effort investigating and recording the stories of Charles Drake Ferris and Warren Angus Ferris. It is remarkable that these writers, unrelated to me, had such fierce passion for history that they would obsessively pursue pieces of information in order to tell their story because they believed that these men had lived lives worthy of sharing. It is through their efforts that my ancestors will remain in the memory of many, including my own and my children.

I would also like to thank the Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee Library for preserving the Ferris-Lovejoy Family papers and welcoming me to labor over them so many times. It is a rare opportunity to hold in your hands, pieces of your ancestors’ writings, providing a window into their lives. For that I am so grateful!

*****NOTE*****

This document was submitted to The Sons of the Republic of Texas in 2020. The organization did not acknowledge receipt of the document and did not comment on it’s content. I did call and receive confirmation that the document was received. The quest to have Charles Drake Ferris to be recognized as a soldier who fought at The Battle of San Jacinto continues.

References: Too long for this post. Available upon request.

Leave a comment