This post lays out years of research done by Walter McCausland in attempt to solve the mystery of Charles Drake Ferris’ disappearance in 1850. Charles was the younger, full brother of Warren Angus Ferris. To avoid any confusion, Warren Angus Ferris had a son also named Charles Drake Ferris (1852-1919), but this post is about Charles Drake Ferris (1812-1850). McClausland obsessively sought information that might provide clues to a Ferris family mystery. The question at hand was if Charles died at sea in December, 1850 or whether he had actually abandoned his family and responsibilities in Buffalo. He would have been 38 years old.

As a young man, Charles had lived his life filled with adventure, excitement, and freedom. He was in Texas starting in late 1835 or early 1836 until the summer of 1836, returning in February 1837 and again in August 1837. It’s estimated that he spent a total of 8- 10 months in Texas serving in the army and surveying with his brother. He formed a deep fondness for the land and dreamed of returning to it with his entire family in tow. However, after resigning from the army in 1837, Charles returned to Buffalo and was permanently weighed down with the responsibilities of caring for his mother, sisters, and his own family. While Warren and Joshua (half-brother) pursued their dreams away from Buffalo, Charles remained and tried to provide for his mother and sisters. In April 30, 1840, Charles wrote to Warren:

Brother Warren:

“We are all well, but Charley has the ague and I a slight touch of liver complaint, nothing much I trust. There is no news of any consequence. Times have never been known so bad, but luckily provisions are low and we get along very well, considering. I should have left for Texas months ago but could not collect money that was due me, and besides have just got the final finish put to the dispute with Henry; ’twas that that has kept me here for nearly four years in spite of all my efforts to close It up. It is now done and mother and the children have 3 acres of land, a little fortune in good times, but now a heavy burden. I have just paid on it some 100$ taxes for the past year, and as much the year previous. We can’t sell at present for any price, so much land has been throw into the market by the bankruptcy of nearly all of the city. It may be several years before it will do to sell, for I would not have them throw away for nothing all they have boon so long struggling to gain.“

“Now that they are sure of something some time or other, I shall if not very much disappointed start for Texas in a week or two, and I wish you would make interest to get me a commission in the regular army unless you have in contemplation some better plan. I have supported of course the family to the best of my ability, brought this suit to a close, and leave then tolerably well provided for. For the season, Hester will remain here, and I must now try to lay in the South the foundation of fame and fortune, If I can get into the service again I will ask no more, for I will make my way up the ladder to its highest round or perish in the attempt, I have not wasted my time here, but have acquired a good deal of knowledge that may be hereafter serviceable.”

Unfortunately, his dreams of Texas were thwarted. In 1846, he wrote another heart-felt letter to Warren describing the heavy burdens he bore and the regrets he felt (to be addressed in another post). In the letter he made clear to Warren that he was still counting on him to locate and purchase land in a specific area in Texas for him to return to, as he felt time was running out. Even then, he had not relinquished his hopes of returning to Texas.

After his disappearance, the family members corresponded with with each other discussing the topic. Letters from Charles’ half-sister, Sarah Lovejoy, suggested that Charles was struggling financially, and in poor health physically and mentally. Sarah wrote that in October of 1849, he allegedly boarded a ship named “Unicorn” in Sydney, Cape Breton, hoping to regain his health in Canada and then head to Texas.

Approximately 5 months later, the family received notice that the Unicorn sank in violent storms off the coast of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia in December, 1850 and Charles was presumed to be dead. According to the owners of the ship, 5 months had passed since the the ship left Sydney, and no word had been heard of her. They considered the vessel had sunk and all passengers were lost at sea.

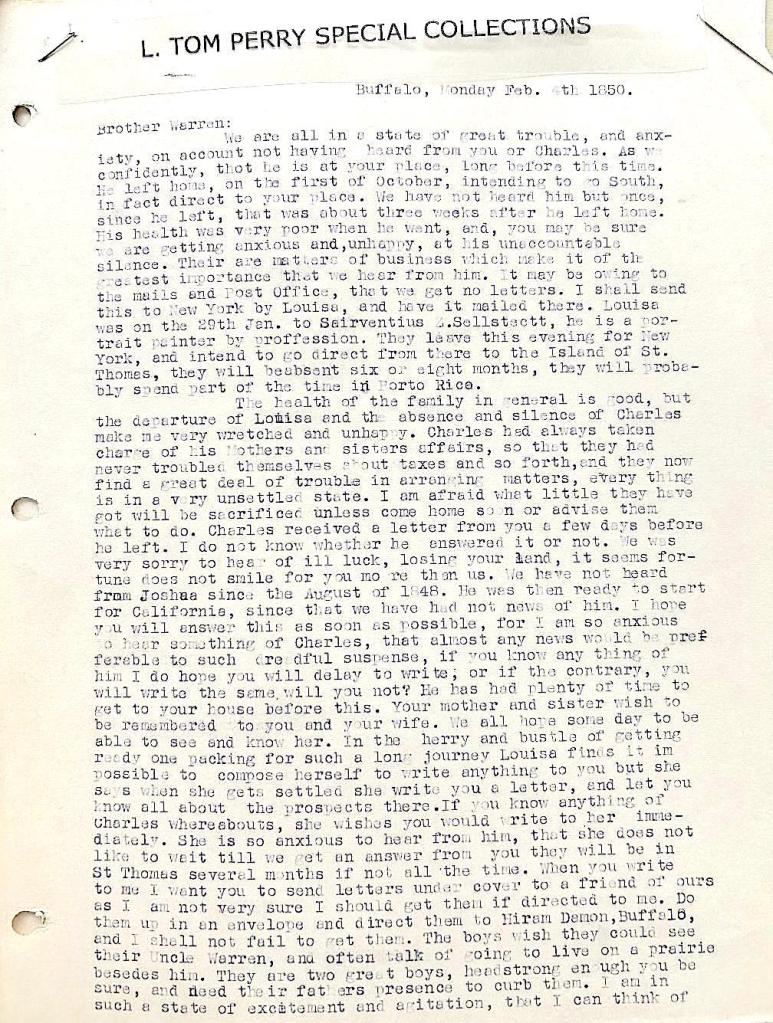

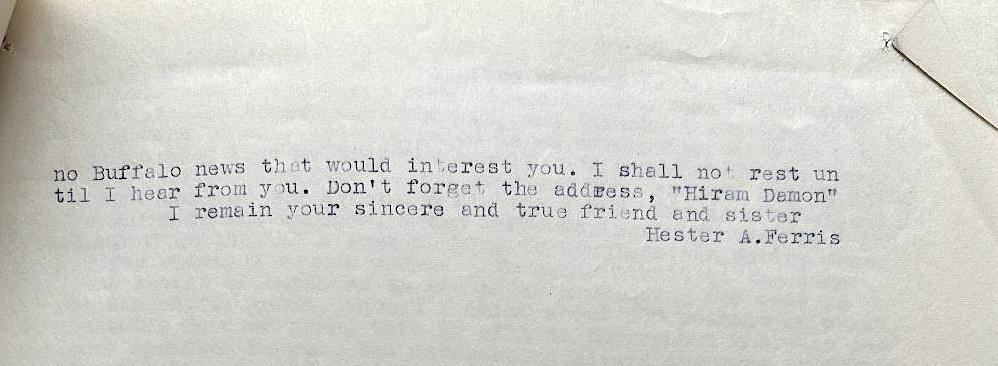

Below: February 4, 1950, Hester Ferris (Charles’ wife), pregnant with their 5th child, wrote frantically to Warren stating “He left home on the first of October intending to go south in fact direct to your place, we have not heard from him but once since he left, that was about 3 weeks after he left home…..Charles received a letter from you a few days before he left.”

After Charles disappeared, his half-brother, Joshua, suggested that he may have “skipped out” and started a new life somewhere else. He was convinced that Charles was a bigamist as well as a man who deserted his family. He claimed that a cousin had told him that Charles had been spotted in Louisville, Kentucky. In 1865, Joshua had his attorneys place a “Missing Persons” advertisement in New York, Texas, Louisiana, Montreal, and California newspapers.

WANTED- Information on whereabouts of Chas. D. Ferris who left Buffalo fall of 1850. Last heard of in St. Peters or Sidney 1851 – supposed to have been married about that time near Chambers Bay under the name of Henry A. Johnson.

In searching for the location of “Chambers Bay”, the only U.S. or Canadian location is in Washington State and oddly, this advertisement was not placed in Washington. It’s possible that there was a defunct town or city by that name, but there’s no information available suggesting that. There is a Chambers County in Texas, but it doesn’t have a bay or town with that name. Also, I couldn’t find credible sources confirming a Henry A. Johnson connected with Chambers Bay in the 1850s. It’s curious that, in this advertisement, such a specific location and name is given. There’s nothing in the family collection explaining why Joshua came to this conclusion. He must have had some information that he thought was credible.

As the years passed, the family continued to question the whereabouts of Charles. In August, 1855, Warren wrote a letter to his family in Buffalo suggesting that “vessels sometimes are driven far from their course and wrecked upon desert islands where mariners might support their existence for months or even years before an opportunity offered to find a conveyance home. I had hoped that you might hear from him living. If, however, such is not the case, it would be vain to indulge any further hope”. The family still had no answers as to what really happened to Charles.

Walter McCausland found Charles’ disappearance to be an intriguing puzzle and sought evidence that could confirm his death at sea. From 1941 to 1944 he corresponded with family members, maritime, and insurance companies for clues. Somewhere in his research, he determined the Unicorn Charles boarded to have been a barque. The letters below summarize his research.

Below: March 22, 1941, McCauland begins his research by contacting Mrs. George Cannon (Sarah Ellen Ferris Cannon), Charle’s niece, requesting family contact information.

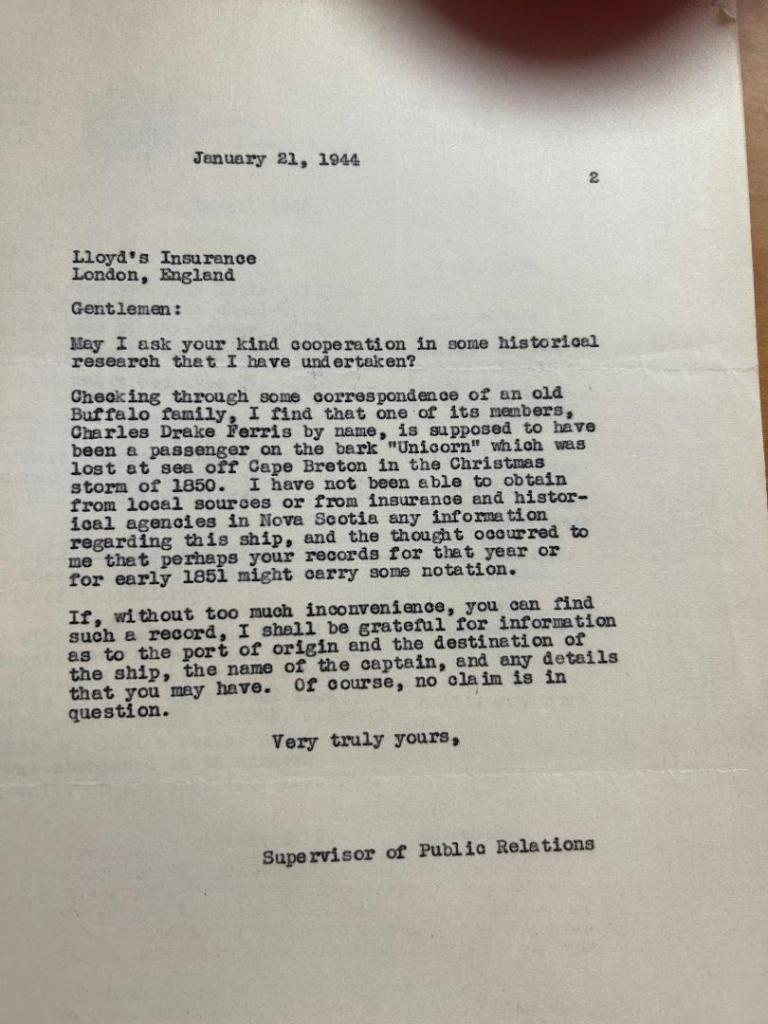

Below: January 21, 1944, Walter McCausland writes to Lloyd’s Insurance in London, England inquiring about records of a barque named “Unicorn” lost at sea December 1850, off Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

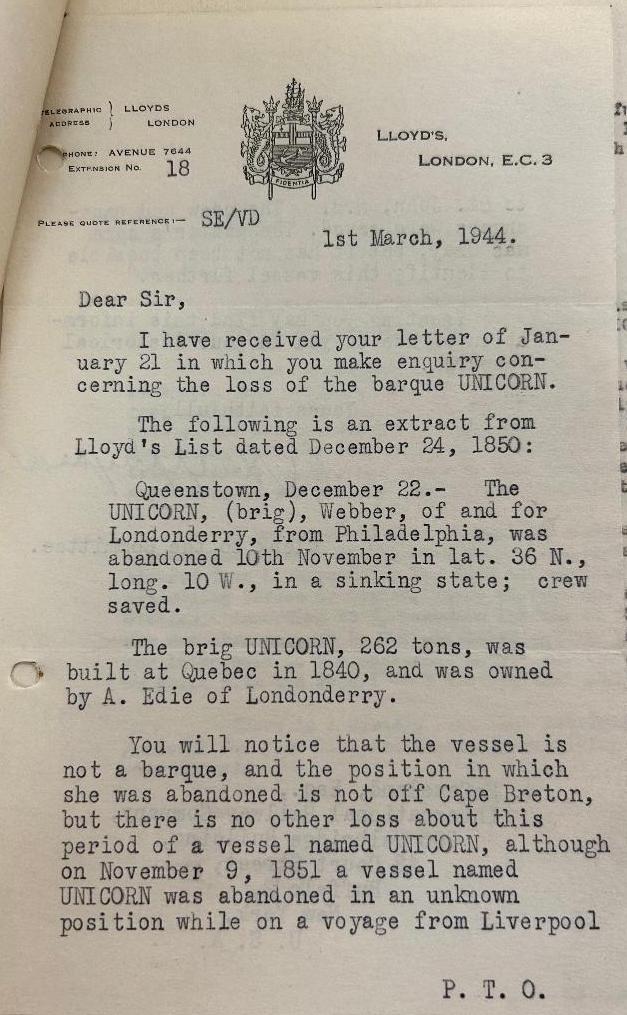

Below: March 1, 1944, Lloyd’s, London responds that the only record of a ship named “Unicorn” was a brig (not a barque) which sank on November 10th, 1850 at a location in the Atlantic Ocean, west of the Strait of Gibraltar and off the coast of Morocco and Portugal, and the crew was saved.

Below: February 12, 1944, McCausland writes to Mr. Wilmot, Passenger Trafficking Manager of The International Railway Company asking if his “Cunard” friends might be able to locate information on a ship named Unicorn. Cunard refers to a historical transatlantic shipping company.

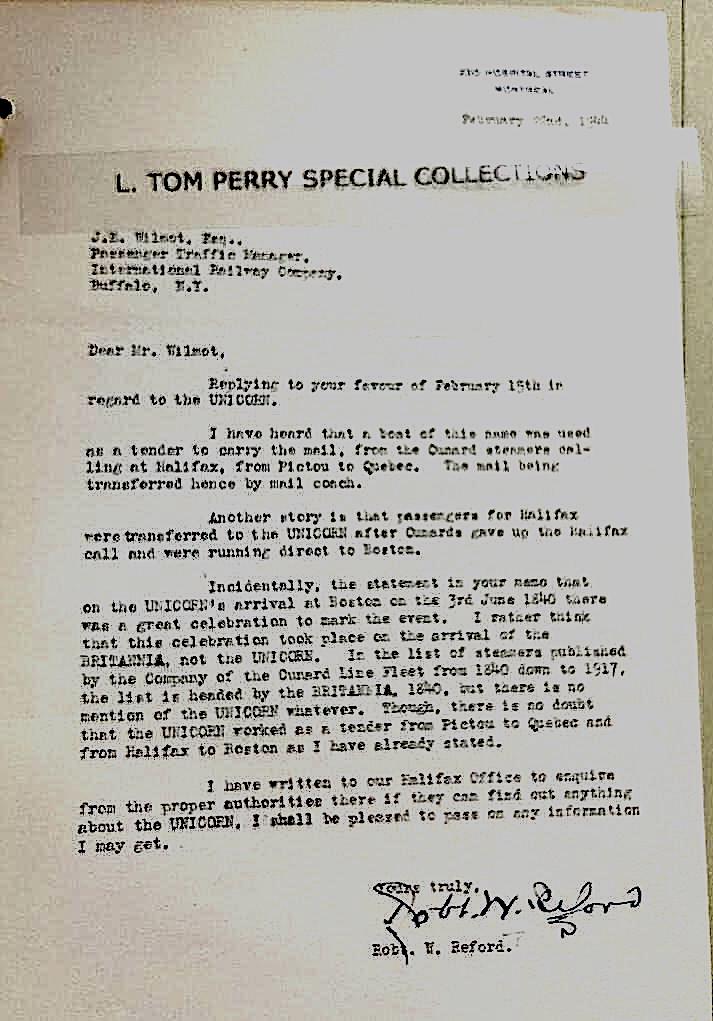

Below: February 22, 1944, Mr. Robert Reford responds to Mr. Wilmot’s inquiry about the Unicorn. Mr. Redford provides possibilities of what the Unicorn may have been used for.

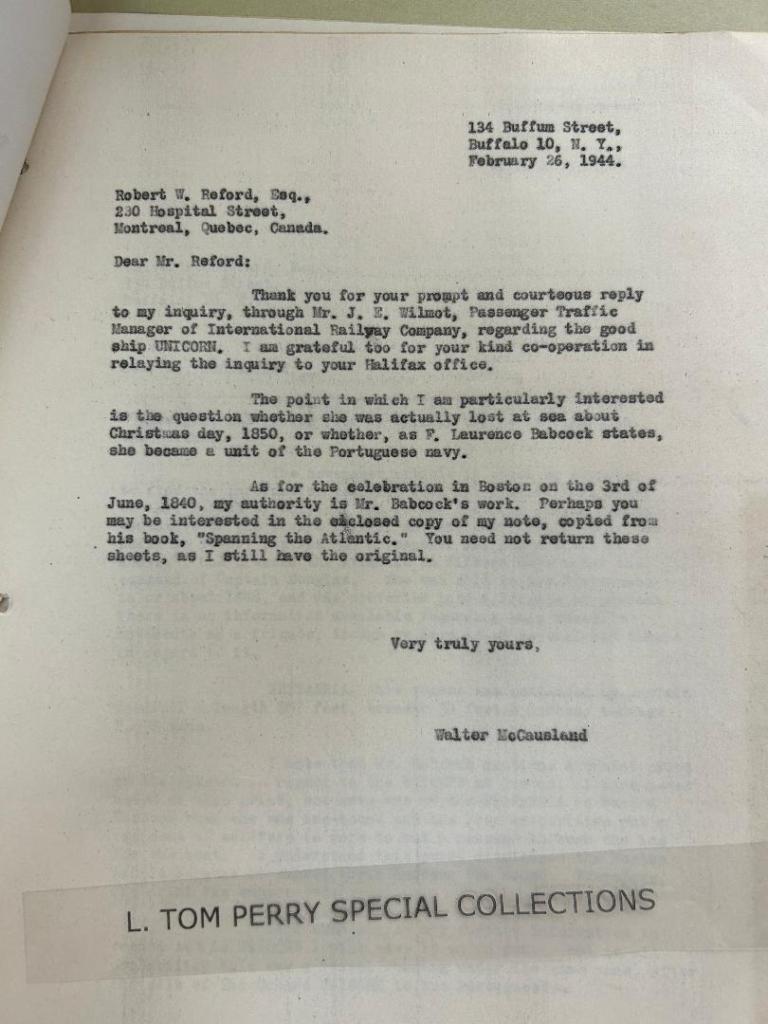

Below: February 26, 1944, McCausland writes to thank Robert Reford for helping with his inquiry about the Unicorn. He asks for confirmation that the Unicorn sank in December of 1850 or if it was sold to Portugal.

Below: March 14, 1944, McCauland writes to Mr. Appleyard of Lloyd’s London stating that it’s unlikely that the two Unicorn ships with maritime records in 1850 are the same Unicorn that sank in December, 1850.

Below: March 18, 1944, Mr. Robert Reford writes to McCausland stating that the Unicorn that was reported to be lost at sea, December, 1850, was likely a vessel using the same name as the two other Unicorn ships that have maritime records.

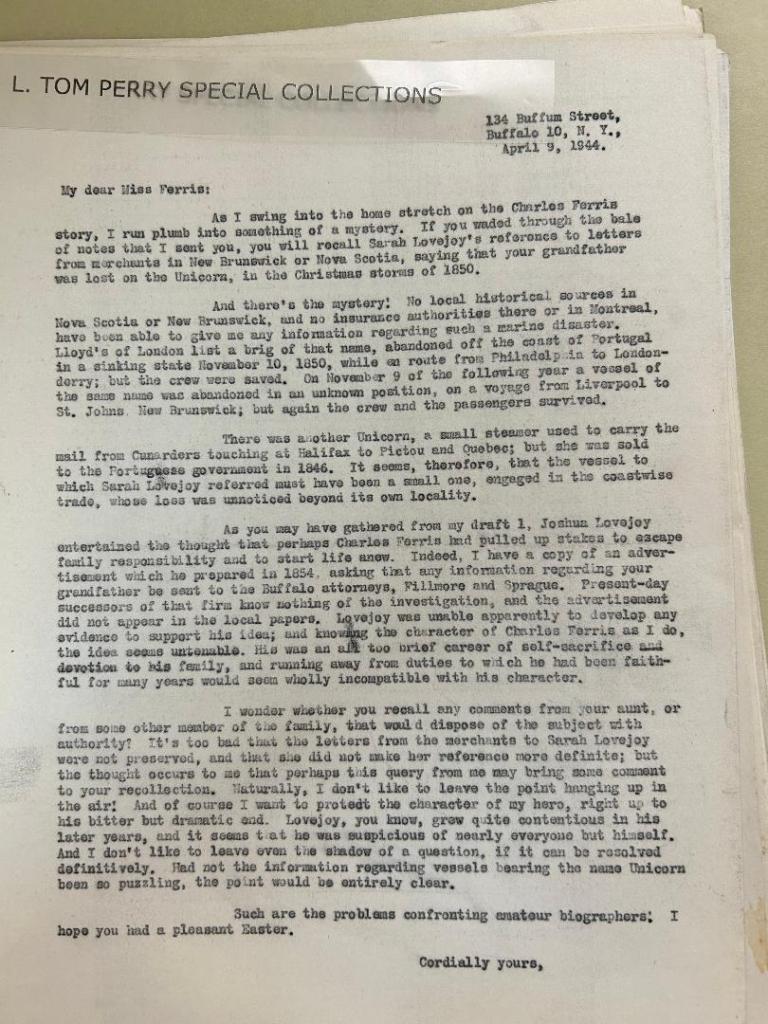

Below: April 9, 1944, Walter McClausland writes to Miss Winifred Ferris (Charles’ granddaughter) explaining that there are no maritime, historical, or insurance records that provide information supporting the story that Charles’ ship, the Unicorn, was lost at sea in the Christmas storms of 1850. He brings up Joshua Lovejoy’s theory that Charles “skipped out”. He mentions an advertisement that Joshua created to place in the newspaper inquiring about Charles’ disapearance. (There is a copy of this in the family paper collections). McClausand asks Ms. Ferris if she recalls any comments made by family about this possibility.

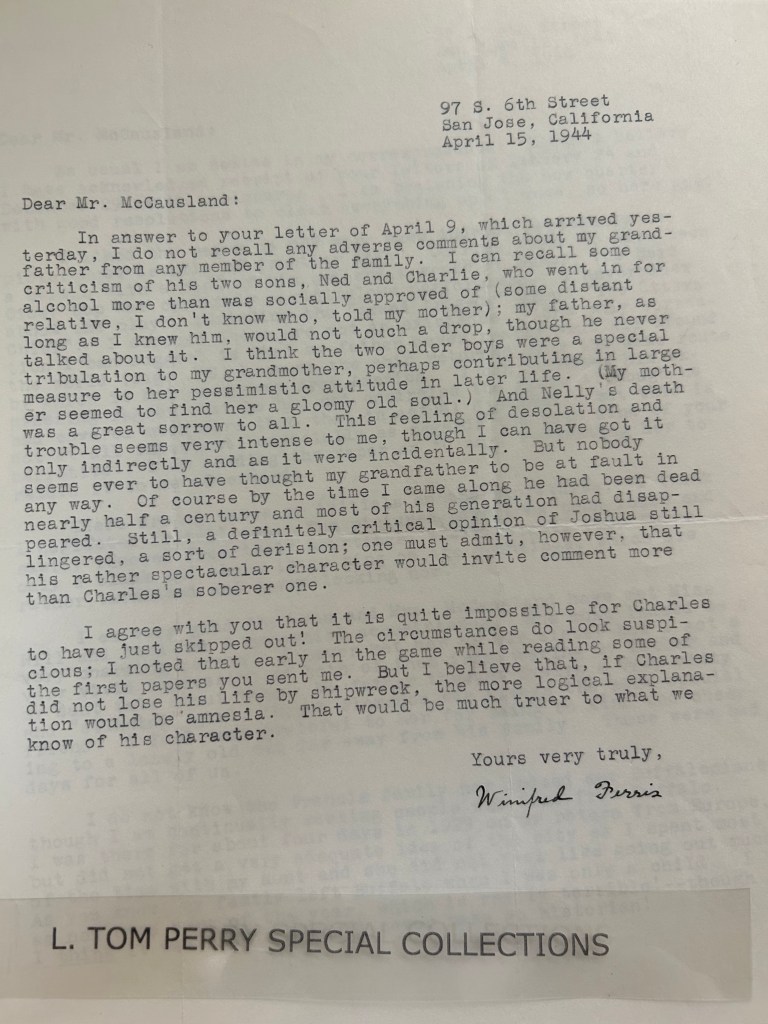

Below: April 15, 1944, Miss Winifred Ferris responds stating that she doesn’t recall any comments from family regarding Charles “skipping out”. She suggests that if he didn’t lose his life on the Unicorn, perhaps he had amnesia.

Below: April 30, 1944, Charles’ granddaughter, Amy Ferris, writes to her sister, Winifred. She states that as a child, there was very little spoken about Charles. She speaks to possible resentment felt by the family for Charles not being present and out “adventuring”.

Below: May 15, 1944, Miss Ferris responds to Mr. McClausland on May 15, 1944. She suggests that perhaps Charles suffered from “amnesia” due to his mental state due to being overwhelmed with financial and family responsibilities. She suggests that Charles may have never gotten boarded the Unicorn at all. She refers to the 1846 letter Charles had written to Warren expressing his life regrets and that he was suffering .

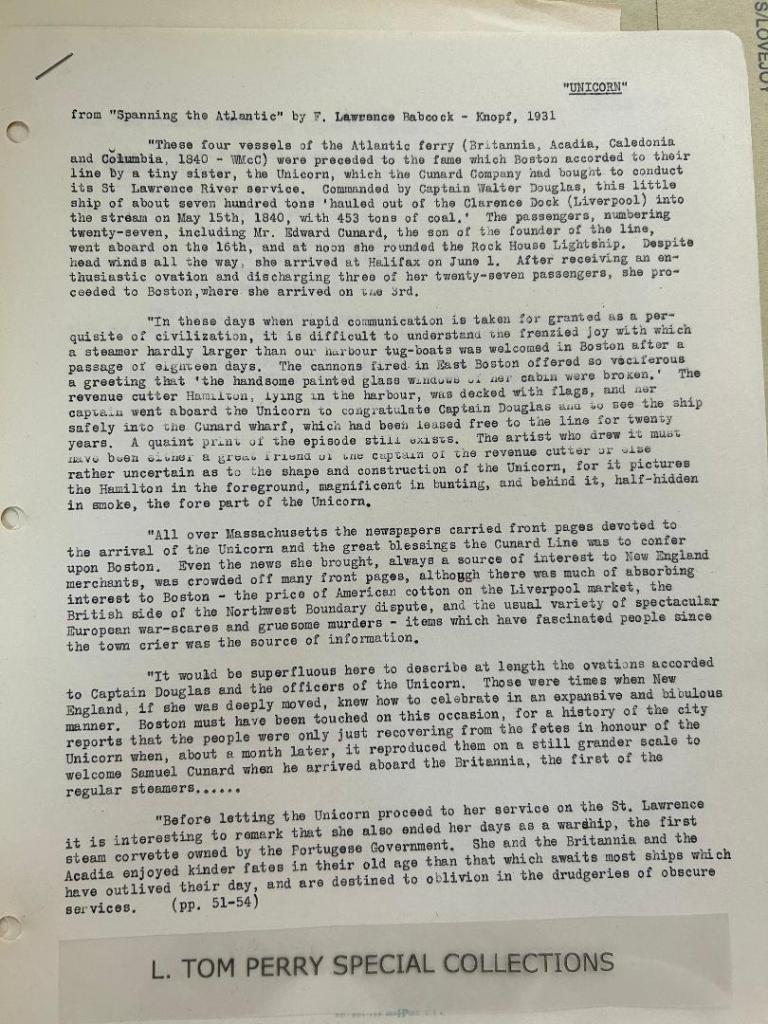

Below: Research collected by Walter McClausland on the “Unicorn” vessel.

Based on the family collection, the letter that announced the fatal news of the Unicorn and Charles wasn’t preserved and it doesn’t appear that anyone sought evidence that the information was valid. In all his research and correspondence, McCausland wasn’t able to find concrete evidence that 1) Charles boarded a ship named Unicorn in Sydney, Cape Breton Island; and 2) that a ship named Unicorn sank in December, 1850 off the coast of Cape Breton. Maritime records indicate that the only ship named Unicorn that sank in 1850, actually was a brig which sank west of the Strait of Gibraltar off the coast of Morocco and Portugal, and the crew was saved.

Thus, the mystery of what happened to Charles has not been solved. The possibility that he never boarded a ship named Unicorn, was not lost at sea, and did abandon his family remains. However, from his writings, it seems that McClausland was not convinced that Charles was capable of doing this. Is it possible that he abandoned his family? He left 2 days after hearing from his brother Warren that his situation in Texas was extremely difficult and disappointing. His wife was about to deliver their 5th child. He had financial woes and tremendous responsibility. Maybe the letter from Warren was the last straw and he was finally pushed too far. One question that comes to mind is where was Charles when he wrote to his wife Hester 3 weeks after he left Buffalo and asked for money and clothing? This strikes me as curious and I wish we had more information.

Charles Drake Ferris (1812 – 1850) had 5 children, Charles Warren, Edward Lovejoy, Ellen May, George Washington, and Sarah Louise. Of the 5 children, only George Washington Ferris had children. His 3 children were named Amy Louise, Laurence Warren, and Winifred Jeanette. I’ve found conflicting and misleading information on several ancestry websites as to their specific descendants and I don’t know what is actually correct. From what I can surmise, both Amy and Laurence had children. I’m not certain if Winifred Jeanette did. FamilySearch doesn’t list any children under her name, however that could also be incorrect. Nevertheless, I’m hopeful that there are direct descendants of Charles Drake Ferris (1812-1850) out there who will find this story and perhaps are curious enough to continue looking for the answer to this mystery. If Joshua Lovejoy was correct about Charles abandoning his family, it’s possible that Charles started a new life and may have had other children. If that were so, perhaps one day someone will pursue DNA testing that will lead them to Charles Drake Ferris as an ancestor and the mystery would be solved. As of today, the search for answers continues.

Today, we have the luxury of typing in a query into Google or ChatGPT and having information at our fingertips. Research is so much easier than it was for McCausland in the 1940’s. I’ve done a little investigating of my own for a ship named “Unicorn” that left Sydney, Cape Breton in 1850. ChatGPT located a a vessel, possibly a schooner, registered in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, in 1850, with tonnage 44 (tons) and CLIP entry 18/1850 and BT 162/20-1, folio 33. Also, the Mahone Bay Museum (ship / boat database) records a vessel named Unicorn built in 1844, with gross tonnage 48, net 44, and a registration dated 1850, with register identifier C850018 in their spreadsheet. In order to keep details complete, I’ve copied and pasted the information from my search. I couldn’t find a source (CLIP or BT) with an on-line microfilm to view, so I’ll request the records that ChatGPT suggested. I’ll also check suggested newspaper sources. Still, this is encouraging news to learn that there actually was a ship named Unicorn recorded to have been in harbor in Sydney in 1850. McCauslalnd was not able to prove that particular detail. If’ I’m able to obtain the historic maritime details, I’ll be able to check dates, locations, crew names and possibly confirm that Charles actually boarded the ship that his family believed he did.

If anyone would like to add to this story, or make corrections, please contact me and I’ll put your information into this blog. I’d love to hear from you!

Below is the ChatGPT information:

1. Registry & basic particulars

- The Crew List Index Project lists UNICORN as a vessel registered in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, in 1850, with tonnage 44 (tons) and entry 18/1850. Crew List Index Project+1

- The same listing shows the record is in BT 162/20‑1, folio 33 (that is, the archival ledger holding crew / registration records for that port in that year) Crew List Index Project

- The Mahone Bay Museum (ship / boat database) also records a vessel named Unicorn built in 1844, with gross tonnage 48, net 44, and a registration dated 1850, with register identifier C850018 in their spreadsheet. Mahone Bay Museum

- Thus, there is good reason to believe Unicorn was a schooner (or at least a small sailing vessel) of ca. 44 tons, built in 1844, and formally registered (or re‑registered) in 1850. Mahone Bay Museum+1

2. Local context & comparisons

- In the same Crew List register (BT 162/20‑1) for Sydney, Cape Breton in 1850, many other small vessels are recorded (e.g. Star, Surprise, Susan, etc.) with tonnages in the 20–90 ton range. Unicorn fits into that local coastal‑ship profile. Crew List Index Project+1

- There is no direct evidence in the accessible digital sources I found that Unicorn was involved in major voyages (e.g. transatlantic) or in famous incidents.

3. What is not known (so far)

- Owner(s) of Unicorn — I did not find a name of the person or firm owning the vessel in the 1850 record in the sources I checked.

- Master (captain) or crew details for Unicorn in that 1850 registry (beyond the registry listing).

- Voyage logs, routes, cargoes, or fate (e.g. whether it was lost, sold, broken up) beyond its registration entry.

- Whether the vessel continued operating for many years after 1850 (or changed name / port) is not yet confirmed in the sources I saw.

4. Possible link / caution

- The Unicorn name also appears for a paddle steamer (RMS Unicorn, launched 1836) in other contexts (e.g. in Cunard line / steamship history) Wikipedia+1 — but that is a very different and much larger vessel, and not plausibly the same as the 44‑ton schooner in Cape Breton.

- The Mahone Bay Museum database suggests the Unicorn was “built in 1844, unknown builder, type: schooner, 48 / 44 tons, registered 1850 (C850018)” Mahone Bay Museum — that entry could well be referring to the same vessel as in the Cape Breton registry, but the listing does not directly connect it to Sydney, Cape Breton.

What next / how to dig deeper

To flesh out more details about Unicorn, you might try:

- Archive lookup of BT 162/20‑1, folio 33

That is the primary ledger in which the 1850 Sydney, Cape Breton ship list (including Unicorn) appears. In that ledger, there might be more than just the name and tonnage — possibly the master’s name, origin, or other remarks. You’d need to see the original or a microfilm / archive copy of that file (in British archives or national record offices). - Nova Scotia / Cape Breton maritime / registry archives

Local archives, provincial archives, or Nova Scotia’s shipping / registry office might hold further registry, port, customs, or shipping records mentioning Unicorn. The Cape Breton Genealogical & Historical Association (CBGen) might have leads. - Newspapers, shipping news columns (mid‑19th century)

Check local newspapers (Sydney, Cape Breton), maybe Halifax or Nova Scotia newspapers, for shipping notices, arrivals / departures, accidents, or sales of small schooners. These sometimes mention vessel names, masters, cargoes, changes in ownership. - Maritime museum / local historians

Contact maritime museums in Nova Scotia (Sydney, Cape Breton, Halifax) or historical societies; sometimes they hold unpublished vessel lists or manuscripts. The Mahone Bay Museum’s listing shows that Unicorn is in their data, so they might hold further documentation on that vessel. - Lloyd’s Register / shipping registers / registry volumes

Although small vessels like a 44‑ton schooner may or may not appear in large-scale registers, checking periodical maritime registers (mid 1800s) might yield a listing or at least a cross‑reference if the vessel traded beyond local coasting.

Leave a comment